Introduction

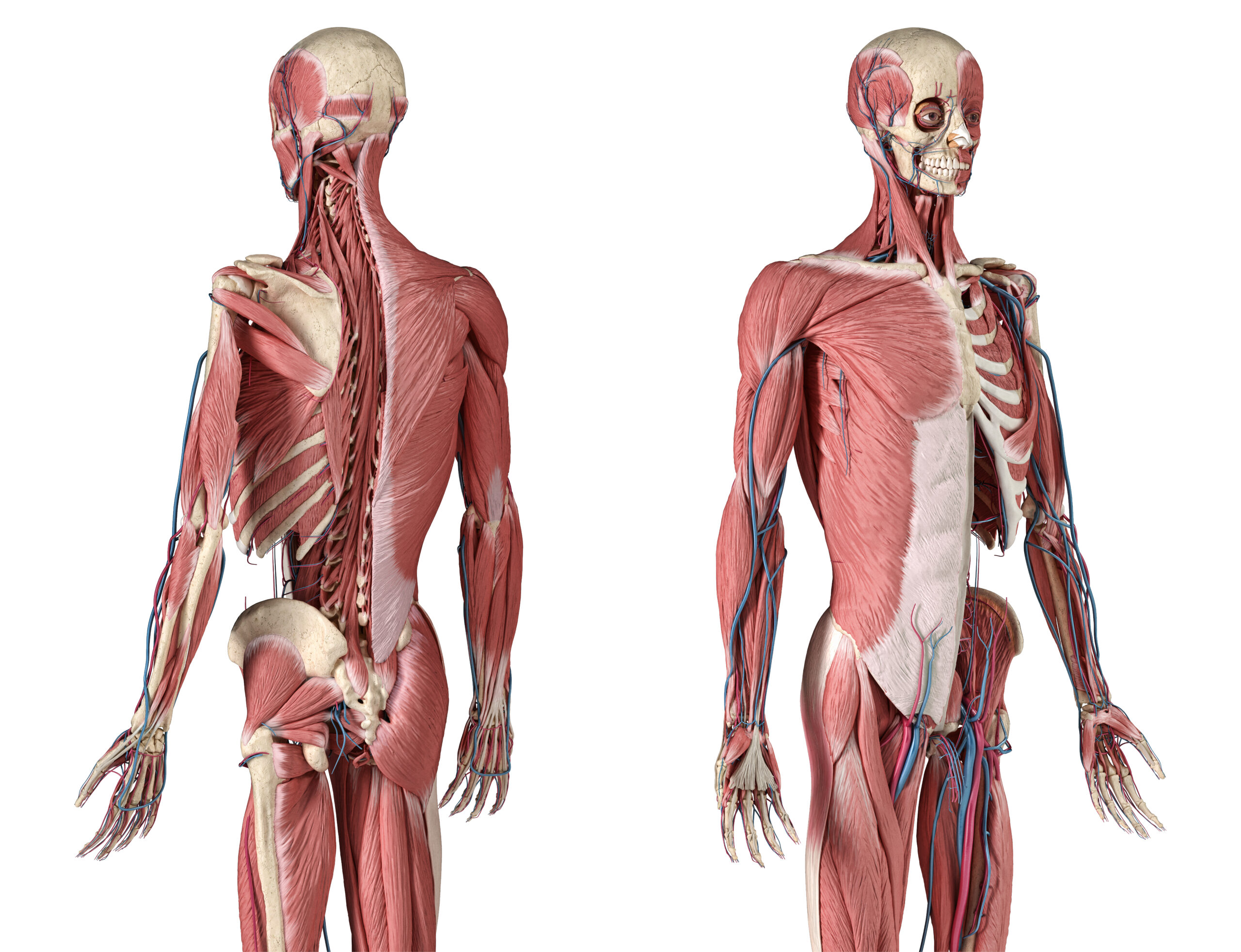

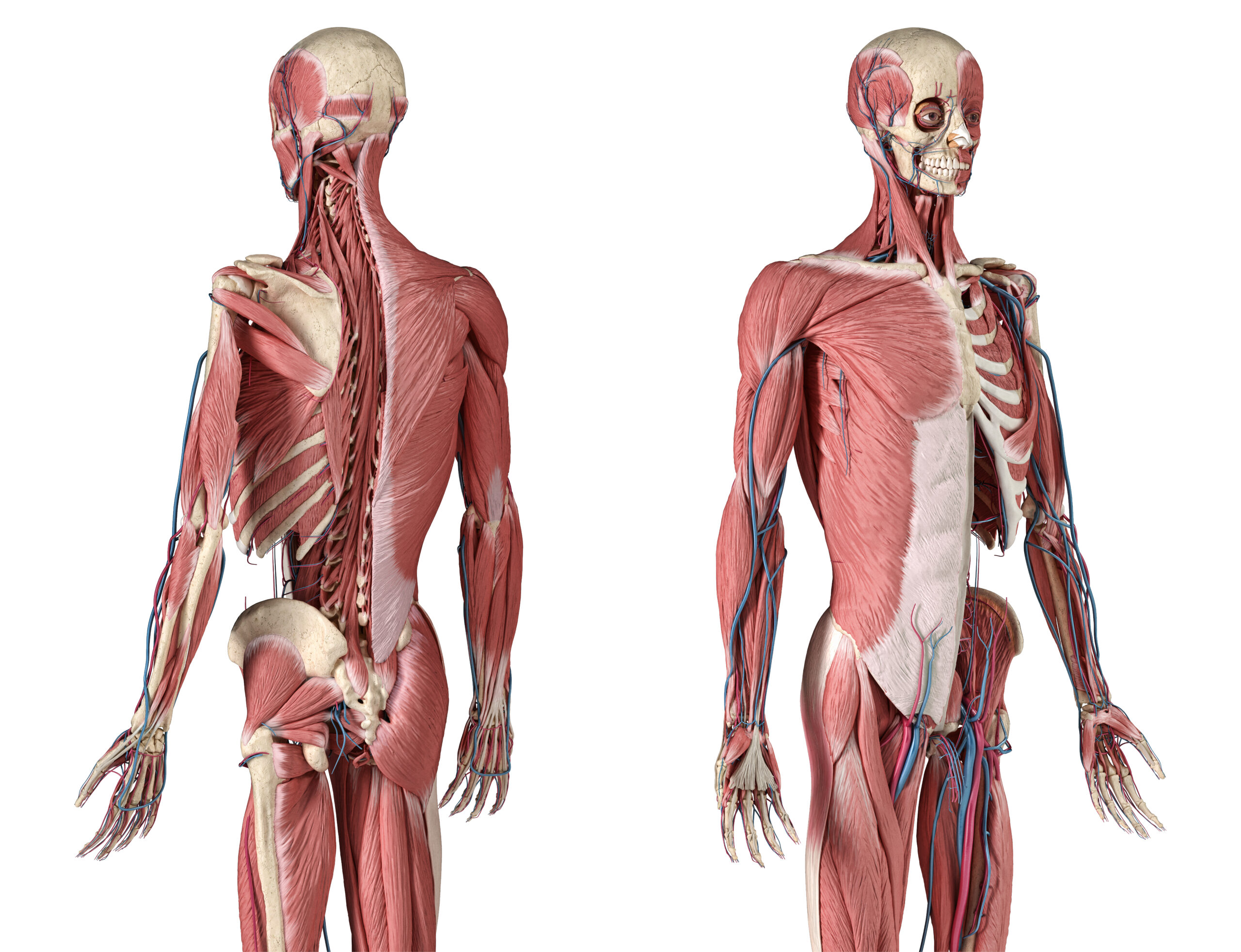

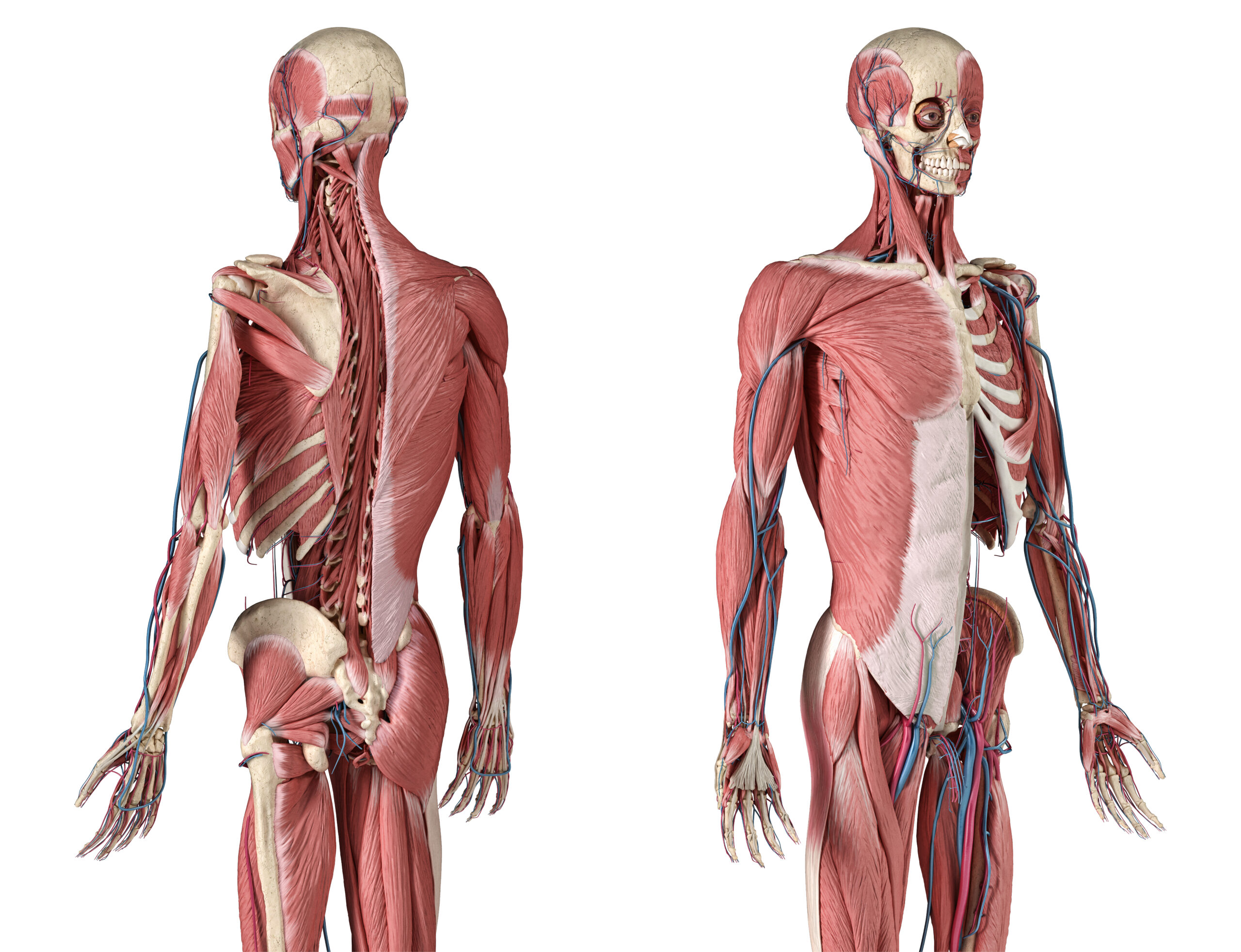

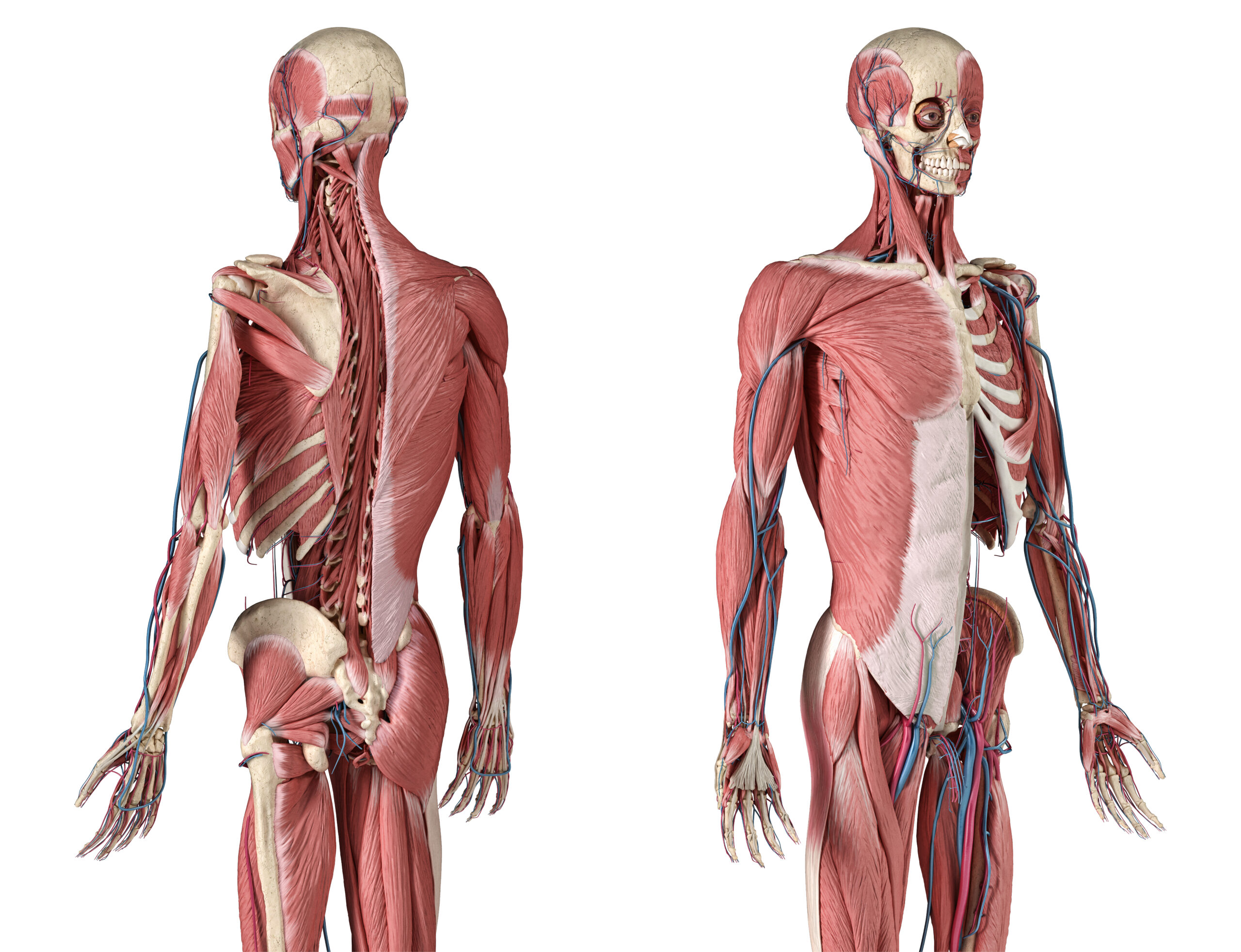

Understanding the intricate web of muscles around your spine is like unlocking the secret to its strength and flexibility. In this guide, we’ll dive deep into the core muscles that hold the key to a healthy and agile spine.

Core Muscles

The Backbone of Stability When we talk about core muscles, we’re essentially talking about the muscles that have a direct impact on your spine’s health and stability. Let’s break them down for a better understanding of how they work together to keep your spine in top shape.

These muscles, nestled deep within your core, act like your body’s own internal support system. They stabilize your spine, allowing for controlled movements without compromising on stability.

Task: Ever wondered why you feel so steady when you stand up straight? That’s these muscles kicking in to keep your spine solid as a rock. Try standing up and feel them in action.

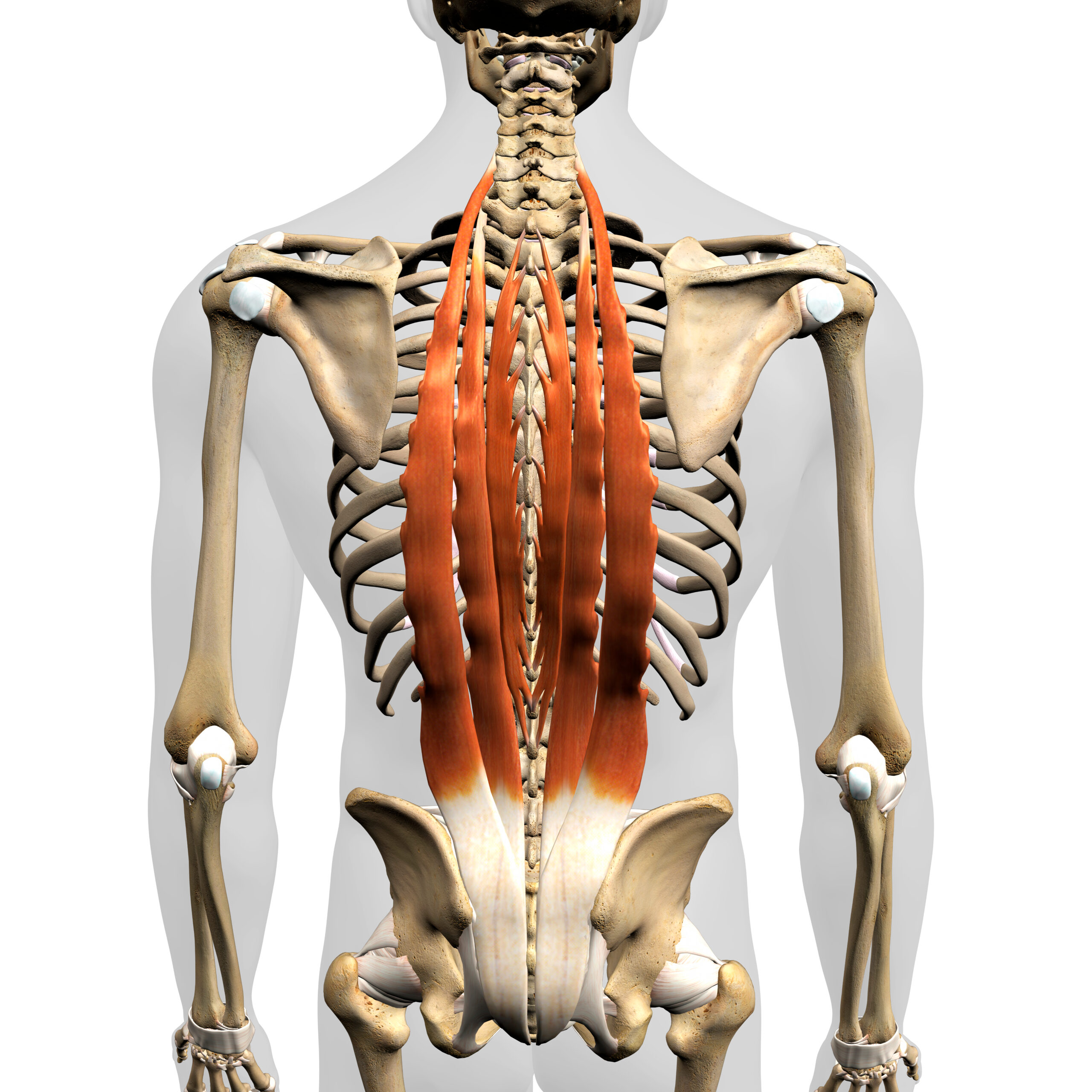

Multifidus: Think of the Multifidus as the backbone’s best friend – thick, strong, and always there to lend support. Regular movement keeps them lean and mean, ensuring your spine stays healthy and happy.

Task: Give these muscles some love by incorporating movements that activate and strengthen them. Your spine will thank you later.

These little guys might be small, but they play a big role in keeping your spine flexible and agile. They’re like the lace-up corset of your spine, providing support without restricting movement.

From your neck to your thoracic spine, the Semispinalis muscles are like the unsung heroes of your core. They work tirelessly to keep your spine stable and mobile, no matter what life throws your way.

Picture these muscles as the sturdy pillars holding up your spine. They’re not just there to look pretty – they’re essential for preventing your spine from bending too far forward and causing injury.

Task: Stand up and feel these muscles engage as you lean forward slightly. Notice how they kick into action to keep your spine safe and sound.

This is obviously the longest one due to its name! To the side (lateral to) of the semispinalis muscles. Travelling from rectus abdominus to the transverse process.

(ilio – from the ilium costalis – to the ribs) – attaches from the most lateral portion of ribs, to the sacrum, the iliac crest, spinous & transverse processes.

The most medial sibling of the group, splits into spinalis dorsi, spinalis cervicis & spinalis capitis. Travelling into the spinous processes & occiput at the back of the head.

Meet the spine’s notorious troublemaker – the Quadratus Lumborum. Despite its reputation, it’s actually crucial for maintaining spinal alignment and keeping you moving with ease.

Task: Pay attention to how your spine feels as you lift one hip. That’s the Quadratus Lumborum at work, ensuring your spine stays straight and strong.

This group is often considered ‘the core’ by clients since their focus is on the front & sides of their torso or the parts they can see.

They all dream of a 6 pack stomach & see adverts about how they can get one in 12 weeks or even 6 weeks or if they follow someone with abs showing on Instagram. You can even download an app that superimposes abs onto your photo…for goodness sake!

The ‘abs’ are written about in magazines as an area to focus on when considering strengthening the core for that washboard abs look!

We should understand them better anatomically to understand how to ‘condition’ them for function & therefore result in whatever is achievable realistically in terms of aesthetics.

Anyway, we all have a 6 pack underneath the skin, and they have an important job to do!

Rectus means straight & abdominis relating to the abdomen. Now this could logically be classified as a core muscle. However when looking at its attachments it does not actually attach directly to the spine but instead to the pubic symphysis (behind the pubes), to the xiphoid process (bottom of the sternum) & the costal cartilages of ribs 5-7.

Generally considered as a flexor of the spine (& of course it will flex the spine) however its main purpose is probably to act as part of the ‘hydraulic amplifier’ mechanism. This is where Transverse Abdominis (TA) & the thoraco-lumbar fascia create tension to stabilise the spine when performing tasks that require spinal stability.

The tendinous junctions of rectus abdominis are designed to help mitigate the lateral forces created by the TA contraction and help with the efficiency of the amplifier. (FANTASTIC BOOK –Spinal Engine, Gracovetsky, March 1989).

The Oblique Non-identical Twins (I LOVE the obliques) are considering lateral flexors & again they do assist this action however their role is far more important than that when you study their fibres & the lines of pull they are capable of with the attachments they cling onto….

This layer travels from the front (Anterior) of the iliac crest, lateral half of inguinal (of the groin) ligament, to the thoracolumbar fascia (big diamond shaped fascial sheet on the lower back) onto the costal cartilages of ribs 8-12; Also via the abdominal aponeurosis to the linea alba (the fascial line down the middle of the tummy of the middle of that 6 pack!)

External surfaces of ribs 5-12. … At the midclavicular (middle of the clavicle) line medially & spinoumbilical line inferiorly, external abdominal oblique continues as an aponeurosis via which it inserts to the linea alba, pubic tubercle & anterior half of iliac crest.

(or unmoving point) of the TA muscles is on the costal (rib) margin, iliac crest, & inguinal ligament. The insertion (or moveable piece) of the TA muscles is located on the xiphoid process, symphysis pubis, & linea alba….hopefully by now we are starting to remember some of these terminologies!

See pelvis CLICK HERE

Greek word diaphragma meaning partition or barrier. Primarily it is attached to the sternum at the xiphoid process, the lower six ribs & the spaces in between, also the lower part of the spine. … The spinal attachment is in the upper lumbar section. The diaphragm’s insertion point is called the central tendon.

No one muscle, or muscle group, is more important than any other. Many will talk of Transverse Abdominis (TVA or TA) & Multifidus as the most important muscles in the core, but if only one group or muscle of the full range of stability muscles is not functioning correctly, then the trunk is unstable.

(Cholwewicki and McGill, 1996, O’Sullivan et al, 1997, 1998, Allison et al, 1998)

Trunk or core stability in motion should be a reflex reaction as opposed to a conscious effort….like core stability training.

The core muscles are often inhibited in cases of low back pain.

Psoas Major & also Latissimus Dorsi could (& probably should) be deemed ‘core’ muscles based on their involvement in trunk/spine stability & connecting the upper & lower body

Understanding your core muscles is like having the keys to a strong and resilient spine. By giving them the attention they deserve through targeted exercises and movements, you’ll not only improve stability but also reduce the risk of injury and keep your spine functioning at its best.